After more than 25 years of investing professionally, I’ve come to the conclusion that options provide some of the best tools to grow wealth while also helping to protect against losses.

Of course, just like any tool, the true value lies in how options are used. And therein lies the rub. Options have earned a bad reputation because too many unskilled investors have picked up these tools and used them improperly, only to be injured when the tool behaved exactly the way it was designed to.

I’m sure a similar outcome would happen if you put a table saw in a room full of children, or even if you let ME loose with a wielders torch! Powerful tools can be dangerous when handled improperly. But in the hands of an experienced professional, they can be incredibly productive.

Today, I want to show you the ins and outs of one of my favorite option strategies. And while some of the details may be a bit tedious, I’m sure that when you finish reading this tutorial, you’ll be well on your way to consistently using options skillfully.

Let’s jump right in!

Calls and Puts — The basics of Option Contracts

At their most basic level, option contracts are exactly what their name implies…

- A contract between two different traders…

- Giving you an option to buy or sell shares of stock.

Option contracts are divided into two main categories. Calls and Puts.

Owning a Call Contract gives you the right to buy shares of stock at a specific price.

Owning a Put Contract gives you the right to sell shares of stock at a specific price.

Both call contracts and put contracts trade on an exchange just like shares of stock. So there is nearly always a listed price for buying or selling one of these contracts. And there are option contracts available for most all widely traded stocks.

For each stock, there can be dozens (or even hundreds) of different option contracts. The difference between these contracts depends on a few key features that are pretty easy to understand once you get used to them.

In addition to the difference between calls (the right to buy shares) and puts (the right to sell shares), there are a few other key factors.

The expiration date tells us how long an option contract is in effect.

When you buy an option contract, there’s a limited amount of time that you have a right to buy or sell your shares. Once the expiration date passes the contract “expires” and you no longer have the right to buy or sell shares.

Traditionally, each stock has had option contracts that expire on different months. And the monthly option contracts expire when the market closes on the third Friday of each month.

More recently, exchanges have listed weekly option contracts that expire on Friday of each week. For the most liquid stocks, there are usually 3-4 different choices for this Friday, the Friday one week from now, the Friday two weeks from now and so forth…

An option contract’s strike price represents the price you’ll be able to pay for your shares of stock if you buy a call contract… or the price you’ll be able to receive for your shares if you own a put contract.

Remember, call options allow you to buy shares of stock for an agreed upon price. That price is the strike price. The same term is used when you buy a put contract (giving you the right to sell shares at the strike price).

For actively traded stocks there are dozens of different strike prices available. So you can pick a contract with a strike price near where the stock is trading today… or one with a strike price that is well above (or well below) where the stock is currently trading.

As you’ll soon see, your choice of which strike price and which expiration date you’ll use can make a very big difference in how much profit you can accumulate, and how reliable your trades will be.

It’s important to note that each option contract represents 100 shares. So when you buy a call contract, you’re buying the right to purchase 100 shares of that stock.

Buying and Selling Option Contracts for Speculative Profits

Option contracts are bought and sold on an exchange very much the way stocks are bought and sold every day.

Typically, traders start by buying a contract to open a new position. For every option contract traded on the market, there’s a market price that you’ll have to pay to buy that contract — and/or a market price for selling the contract when you’re ready to do that.

Market prices are listed on a per share basis. But remember, every contract represents 100 shares of stock.

So you’ll need to multiply the listed price by 100 to calculate the full amount you’ll pay to own this contract.

Let’s assume you want to buy a call option contract for International Business Machines (IBM).

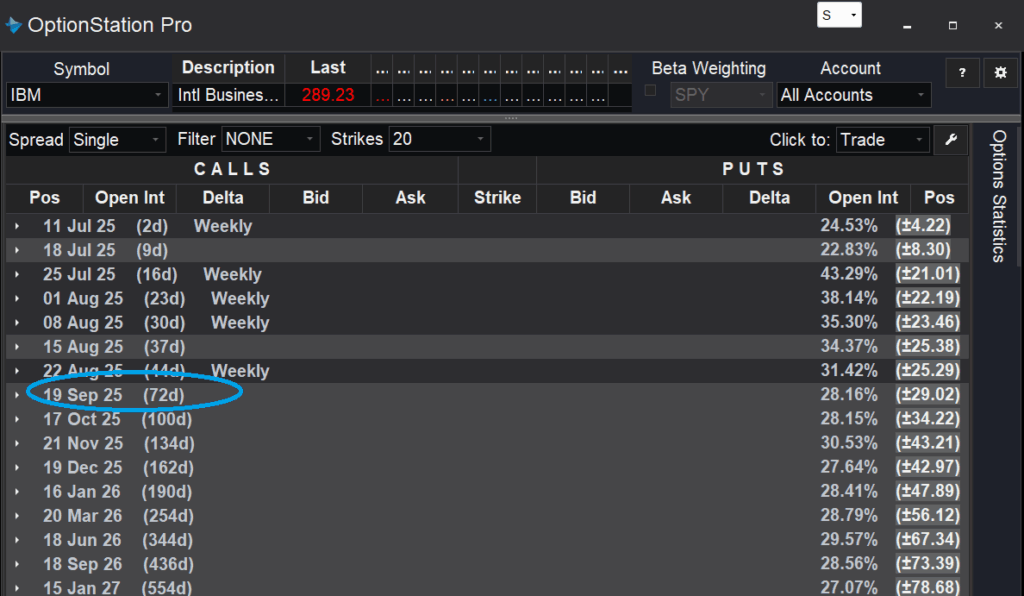

You can use any online brokerage or investing website to pull up an options chain for the stock. Below is a screenshot of a trading platform I use, showing some of the expiration dates available for IBM. (We’ll be looking specifically at the September 19th options for this example).

With this platform, I can simply click on any specific date to get more details on which option contracts are available to buy. In other platforms, there may be a dropdown menu to select an expiration date or a similar feature to find the contract you’re looking for.

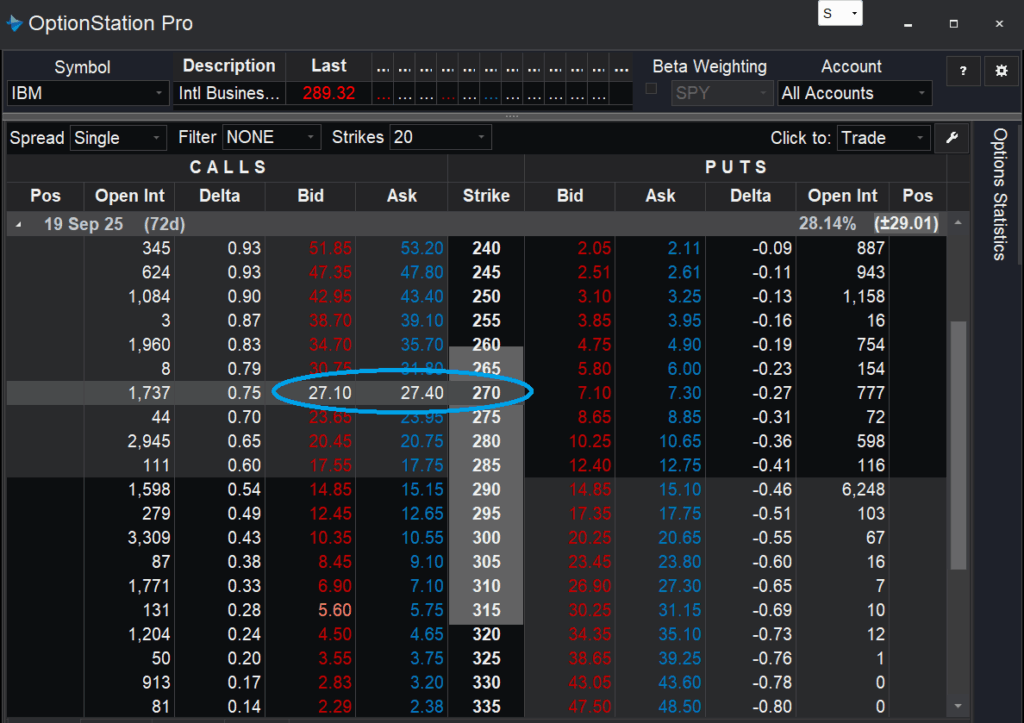

Once I select the September 19th expiration date, I’m able to see the different contracts that are available for me to buy.

Note in this example that the strike prices are listed in the center of this table, with market prices for call contracts on the left, and market prices for put contracts on the right.

I’ve highlighted the IBM September 19th $270 call contracts to show you how to select one specific contract.

Notice that there is a “bid price” and an “ask price” for each contract. This tells you what price you can expect both for buying and for selling this contract.

The “bid price” is the price a market maker is “bidding” for the specific contract. So if you’re selling, you know there is a trader willing to take the other side of your transaction at the bid price. In other words, you can sell an IBM September 19th $270 call contract at $27.10 per share right now.

The “ask price” is the price a market maker is “asking” for the same contract. So if you’re buying, you know there is a trader willing to take the other side of your transaction at the ask price. In other words, you can buy an IBM September 19th $270 call contract at $27.40 per share right now.

Don’t forget, each contract represents 100 shares. So if you buy this contract at $27.40, you’ll be paying $2,740 (plus any fees or commissions) for each contract.

Once you own a contract, it’s easy to sell by selecting the very same contract and choosing the “sell” feature in your brokerage account. Most accounts make it even easier by allowing you to simply click on your position and then hit “sell” to make sure you’re selling the right contract.

One final thing to keep in mind is that some brokerages require you to designate either “to open” or “to close” when placing an option trade.

“To Open” simply means you’re buying a new contract that isn’t currently in your account. So you’re opening a new position. (Select this even if you’re buying an additional contract to go along with other identical contracts you may already own in your account.)

“To Close” means that you’re closing out one or more of the contracts you already hold in your account.

This designation helps the exchanges keep track of how many contracts are actually held between different traders.

Option prices and How they Change

[Quick Note: In this section we’re going to get into some academic details of how options are priced. You don’t NEED to understand all of these details to trade options. But I think it helps to understand why options work the way they do. The more you understand, the more comfortable you’ll feel when placing these orders!]

Market prices for buying and selling your option contracts depends on a few different variables. Option prices are tied to the price of the underlying stock. But there are some important nuances for how these prices are connected.

“In the Money” Option Contracts

The first thing to note is whether an option contract is “in the money” or “out of the money.”

An option contract is considered “in the money” if there is value in exercising your option to buy or sell shares at the agreed upon price.

Remember, call contracts give you the right to buy shares of stock at a certain price.

If you have the right to buy shares at $50 and the market price is $60, you can use your right to buy 100 shares at $50 and then sell those shares in the open market at $60. You’ll pocket $10 per share (or $1,000 per 100-share contract) for this transaction.

So with call contracts, an option is “in the money” if the stock’s market price is above the options strike price.

For put contracts, an option is “in the money” if the stock’s market price is below the options price.

That’s because if you have the right to sell shares at $50, but the market price for that stock is $40, you could buy shares today at the market and immediately sell them at $50. Again, you’d pocket $10 per share or $1,000 per 100-share contract.

In the table below, you can see a series of Microsoft (MSFT) option contracts for the September 19th expiration date. Microsoft is currently trading just above $500 per share.

Notice that call options with a strike price below the current $501.85 market price for MSFT are “in the money.” And put contracts with a strike price above the $501.85 market price for MSFT are also “in the money.”

Option contracts not “in the money” are considered “out of the money.” We’ll discuss some of these contracts another time when we talk more about a more conservative income approach.

For more aggressive growth trades, I primarily focus on “in the money” option contracts because of the unique way option prices react to movements in the underlying stock price.

Two Values in an Option Price

The market price you’ll pay to buy a call contract or a put contract can be divided into two categories:

- Intrinsic Value — The value of a contract if it were to be exercised right now.

- Extrinsic (or Premium) Value — The additional cost of a contract above its intrinsic value.

Let’s look at an example to see both of these values in play.

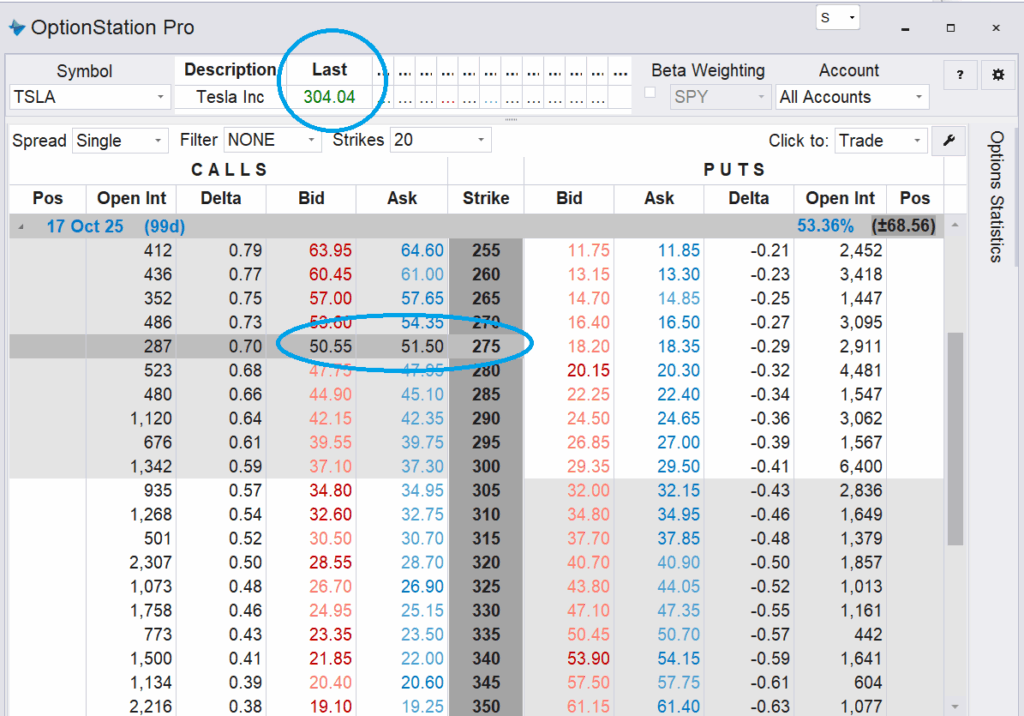

Here is a screen shot of Tesla Inc. (TSLA) option contracts set to expire on October 17th. At the time of writing there are 99 days left until expiration.

Notice the market price for TSLA stock is $304.04. I’ve highlighted the $275 call contracts which can be bought for $51.50.

First, let’s calculate the intrinsic value for the TSLA $275 call contract.

- These calls give you the right to buy shares of TSLA at $275.

- You can sell those same shares at the market price of $304.04.

- Your profit on this transaction would be $29.04 — this is the intrinsic value for the call contracts.

If the intrinsic value is $29.04 and the market price to buy these call contracts is $51.50, that means the extrinsic value — or premium is $22.46 per share.

This is the extra amount you have to pay on top of the underlying value of your option to buy at $275 and sell at $304.04. Traders are willing to pay this higher premium because there’s a chance that shares of TSLA could trade higher between now and when the October calls expire.

So at some point in the future, the intrinsic value could be much higher. And that’s the reason traders are willing to pay a market price above the intrinsic value to buy a contract.

The amount of premium varies depending on how volatile traders expect a stock price to be, how much time is left until the option contract expires, and a few other variables.

For put contracts we can use a similar calculation.

Here is a screen shot of Spotify Tech (SPOT) option contracts set to expire on September 19th. At the time of writing there are 71 days left until expiration.

Notice the market price for SPOT stock is $715.23. I’ve highlighted the $800 put contracts which can be bought for $112.15.

First, let’s calculate the intrinsic value for SPOT $800 put contract.

- These calls give you the right to sell shares of SPOT at $800.

- You can buy those same shares at a market price of $715.23.

- Your profit on this transaction would be $84.77 — this is the intrinsic value for the put contracts.

If the intrinsic value is $84.77 and the market price to buy these put contracts is $12.50, that means the extrinsic value — or premium is $27.38 per share.

These different values are important for selecting which contracts to use for our aggressive trades.

Now that we’ve covered some of the basics for how option contracts are priced, let’s look at the best option contracts for our aggressive growth trades!

Selecting Contracts with Great Reward-to-Risk Qualities

I like to think about my aggressive option trades as “taking the elevator higher” when they’re profitable, and “taking the staircase lower” when they don’t work out. In other words, profits accumulate quickly, and losses tend to be more gradual.

The way we set up these favorable reward-to-risk trades is by choosing in the money option contracts that will give us the most benefit, and at the same time will help to buffer our potential risk.

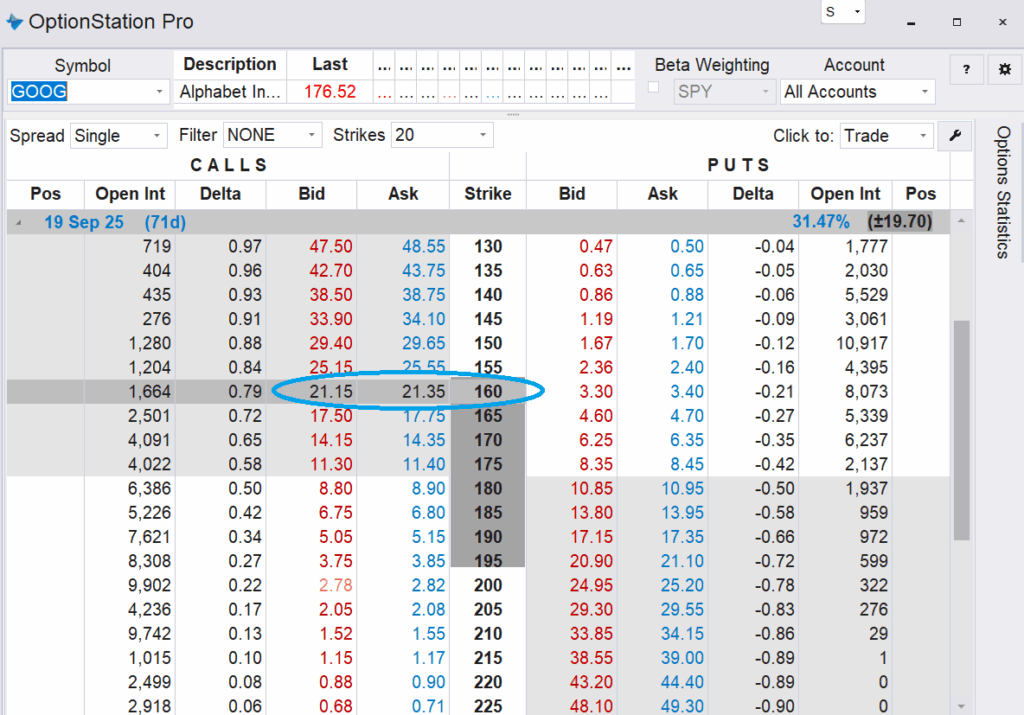

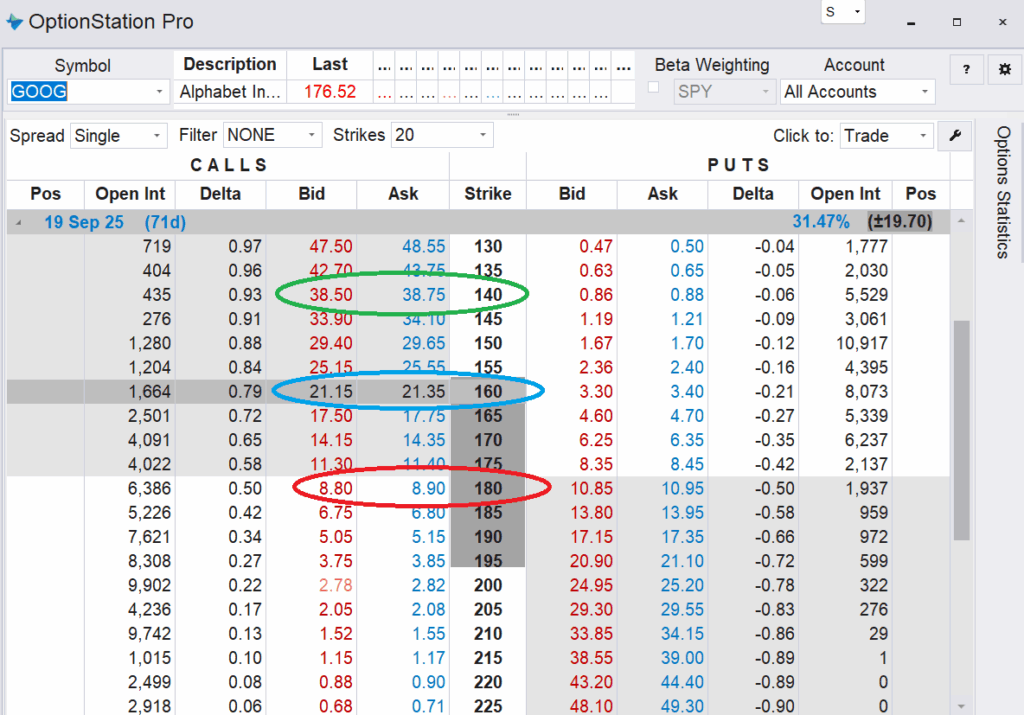

Let’s take a look at some call contracts for Google parent company Alphabet Inc. (GOOG) to see how these trades work.

Assume we expect shares of GOOG to trade higher.

We could buy call contracts for GOOG today and if the stock trades higher our call contracts should increase in value. You can see in the option chain below, we can buy the September 19th $160 call contracts at $21.35 per share (or $2,135 per call contract).

Since the stock is currently trading near $176.52 we know that these $160 call contracts have an intrinsic value of $16.52. That’s because GOOG is $16.52 in the money (or $16.52 above the strike price) for this call option.

Which also means that we’re paying an extra premium of $4.83. The two values add up to the market price of $21.35.

Let’s assume we’re expecting the stock to move about $20 in our favor. But there’s also a risk that GOOG could decline by $20 per share as well.

The current option chain gives us some good clues for what to expect if either one of these scenarios were to happen.

First, let’s start with the positive scenario.

If GOOG were to trade $20 higher, we know that our call contract would go from $16.52 in the money right now — to $36.52 in the money after the stock’s rally.

So what would the price be for an option that is $36.52 in the money? We can look at the current option chain to get a good idea of what that price would be!

Notice the GOOG September 19th $140 call contract circled in green. That’s the contract that is currently $36.52 in the money. And we could sell that contract near the bid price of $38.50.

Of course there could be other factors involved (such as time decay, a change in the stock’s volatility and trader expectations). But a rough calculation shows us that if the stock were to move $20 in our favor, we should be able to sell our option contract close to $38.50 per share.

That would give us a profit of $17.15 per share — or $1,715 per contract.

So you can see that on a dollar-for-dollar basis, this trade could capture about 86% of the price move that shares of GOOG made. We only had to invest $21.35 per share (instead of the $176.52 per share that buying the stock outright would have required). And in total, the trade would have resulted in a 80% gain on our investment.

Now that we’ve seen what a successful trade could look like, let’s consider what a decline in the stock would do to our position.

If GOOG were to trade $20 lower, we know that our call contract would go from $16.52 in the money right now — to $3.48 out of the money (meaning the stock would be below our strike price) after the Alphabet’s slide.

Once again, we can look at the current option chain to get a good idea of how a call contract that is $3.48 out-of-the-money would be priced.

Notice the GOOG September 19th $180 call contract circled in red. That’s the contract that is currently $3.48 out of the money. And we could currently sell that contract near the bid price of $8.80.

Once again, there could be other factors involved. When a stock drops, traders are often willing to pay a higher premium for call contracts because volatility is expected to be higher. But let’s use the current $180 call price of $8.80 as a reasonable level for selling our GOOG call contract that is $3.48 out of the money.

Selling our calls at $8.80 would leave us with a loss of $12.55 per share — or $1,255 per contract.

You can see that on a dollar-for-dollar basis, this contract would lose about 63% of the negative price move for shares of GOOG.

That’s because the closer the strike price is to the market price, the more premium is included in the price.

So even when shares move in the opposite direction from what we expect, we’re still insulated from some of the losses which helps to reduce our overall risk.

If you flipped a coin and I paid you $90 for every time the coin landed on heads — and charged you $75 for every time it landed on tails, you’d take as many flips as possible!

That’s the type of reward-to-risk scenario we try to set up with each of our aggressive growth option trades.

Except instead of a coin flip for which stocks to play, I’m using more than two decades of trading experience along with data from many different research services to pick out the stocks I believe have the highest probability of trading in our favor.

We can use a similar approach for stocks we expect to trade lower by purchasing in-the-money PUT option contracts. And we can talk more about these contracts in a separate report.

Maintaining a Formula for Success

The formula that has given me the most success over the decades is to buy option contracts that are relatively deep in the money, have four to eight weeks until expiration, and are tied to stocks that move relatively quickly.

Also, once a stock has had a significant price movement (either positively OR negatively), it helps to adjust to a new in-the-money option contract and start the process over again.

For example, suppose I own a call contract and my stock surges 30 points higher…

I’ll likely sell my call contract and lock in profits on that specific trade. And at the same time, I’ll buy a NEW call contract with a higher strike price.

This new call contract will cost less because of the higher strike price. But it will still allow me to participate in the stock that is trending higher. And since the new contract costs less I have less capital invested (and therefore less risk in the trade).

As an added benefit, I can use some of the profit from my original trade to diversify into a different play, thus benefiting from a new opportunity that the market gives me.

Follow Along With My Personal Trades

If you like this concept of trading but could use some help getting started, consider subscribing to my Speculative Trading Program.

This program is designed to give beginners step-by-step instructions to execute trades exactly like the ones we covered above.

And if you’re an expert trader, you’ll probably enjoy the ever-updated portfolio of real-world trades that I’m placing in my own account each and every week.

Yes, that’s right… I put my own money at risk with the same trades I recommend to you. So you know that I’ve got skin in the game every time I send out a real-time trade alert.

>>Sign up to get real-time trade alerts here!!<<

It’s an exciting time to be an investor and an important time to have tools like this options strategy at your fingertips.

Here’s to growing and protecting your wealth!

Zach